Bronwyn Levvey, Australia has been granted the TTS Scientific Congress Award

Pushing the limits: Successful lung transplantation from a controlled donation after circulatory death donor 9.5 hrs post withdrawal without using EVLP

Bronwyn Levvey1,2, Gregory Snell1,2.

1Lung Transplant Service, The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Australia; 2Medicine, Nursing & Health Sciences, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

Purpose: Currently > 50% of lung donor referrals to our program annually are from cDCD. Between 25-30%% of cDCD donors do not progress to asystole in the protocolized 90min time frame. Predicting which cDCD donor will die in ≤90 mins remains problematic. A 2019 audit of our program’s lung donor referral pool showed that 44% of cDCD progressed to asystole between 90mins-6hours post withdrawal of cardio-respiratory support (WCRS). To facilitate potential utilization of these already accepted cDCD donors, in 2020 our LTx program developed a Delayed Lung Protocol (DLP) where lung donation can occur up to 24 hrs post WCRS.

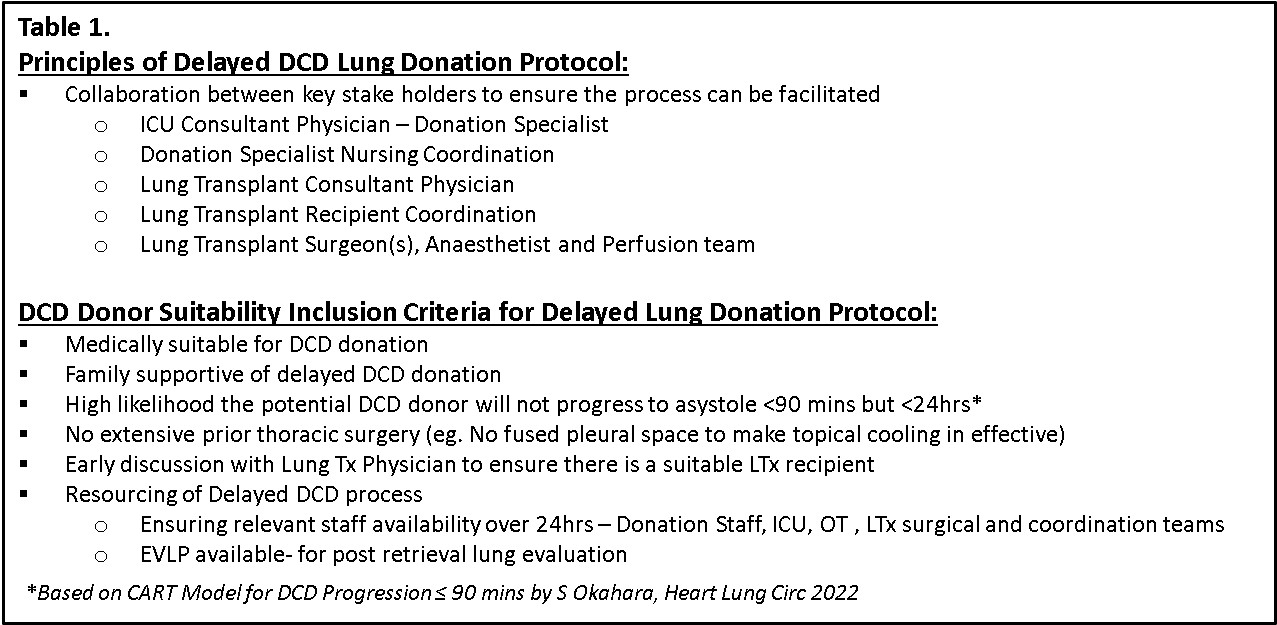

Methods: The decision to use DLP for cDCD lung donation is made at time of donor acceptance (criteria in Table 1). Consent for DLP pathway is specifically sought from donor family as ongoing monitoring of the donor’s BP and O2 saturation post-WCRS beyond the protocolized 90min is required. When systBP ≤75, the donation coordinator contacts recipient coordinator and operating theatre (OT). Once asystole occurs and death is certified, the donor is re-intubated and if no OT is available, intercostal catheters (ICCs) are inserted bilaterally into the pleural space to initiate topical cooling (TC) of the lungs, minimizing the potential effects of warm ischemia. Ex-vivo Lung Perfusion (EVLP) may also be required to assess the lungs. TC and EVLP allows 4-6 hours extra to plan for the donation operation and LTx coordination. LTx recipient selection is made prior to WCRS in cDCD donor based on routine LTx recipient selection criteria.

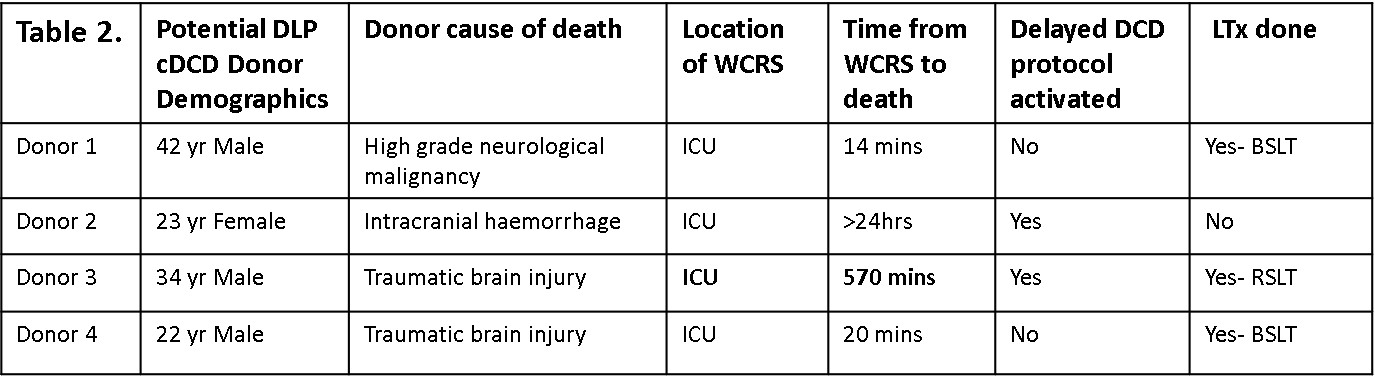

Results: Between 2020-2023, 55/88(63%) accepted cDCD donors progressed resulting in LTx. 4/88 (5%) donors were considered for DLP (Table 2). Donors 1 & 4 progressed quicker than predicted resulting in 2 LTx. Donor 2 died>24hrs post-WCRS- no LTx. Donor 3 had hemodynamics that were stable for 8.5hrs (systBP>100, O2 sat >70) then steadily to asystole by 9.5hrs post-WCRS leaving <1hr to mobilize the OT and LTx surgical teams. Due to immediate availability, the donor was transferred to OT without ICC’s/TC being used, was re-intubated in OT, surgeon visualized lungs & only right lung (RL) was viable. RL was flushed with perfadex, explanted and stored on ice for 3hrs (total warm ischemic time =42 mins). Of note, EVLP was not utilized. The recipient (62 yo male, Dx IPF) underwent R-SLTx with no primary graft dysfunction, 3 day ICU stay and 15 day total hospital stay. Despite excellent early outcomes, unfortunately the recipient died on day 902 from disseminated fungal sepsis originating in native left lung.

Conclusions: Whilst TC and EVLP may minimize the impact of warm ischemia and aid in lung evaluation, successful lung donation and subsequent LTx from a cDCD donor 9.5 hrs post-WCRS was possible without their use. Using a DLP for cDCD enables more lung donors to donate, but does requires support and cooperation between ICU, OT, donation and transplant teams to facilitate the donation process.