Noble S S Gracious, India has been granted the TTS Scientific Congress Award

A performance review of the cadaveric organ donation program in an Indian State

Noble Gracious1,2,3, Satyajith Roy2,4, Binoy Mathew2, Saranya S2, Visakh V2, Thomas Mathew2.

1Nephrology, Government Medical College, Alappuzha, India; 2Health and Family Welfare, Kerala State Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation, Thiruvananthapuram, India; 3Public health, SCTIMST, Thiruvananthapuram, India; 4Operations and Management, Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore, India

Introduction: Even after 30 years of introducing the Transplantation of Human Organ and Tissues Act, the cadaveric organ donation rate in India lies below 1 per million population. The allocation policy has mostly benefitted the patients registered in private hospitals as most of the public hospitals do not have a transplantation facility (except for kidneys). We analyze the donation and transplantation data for an Indian state(Kerala, South India) with nearly 35 million inhabitants to study the demand-supply gap and the disparity in organ allocation.

Method: Background data from 2012 to 2023 was downloaded from the state’s donation and transplant registry system. The data captured details about all patients registered for cadaveric organ transplants, all deceased donations, and the allocation of organs from deceased donors in different hospitals across the state. We considered only solid organs within the scope of this study. (Government of Kerala permission and IEC approval obtained).

Funded by the State Health System Resource Centre,Government of Kerala

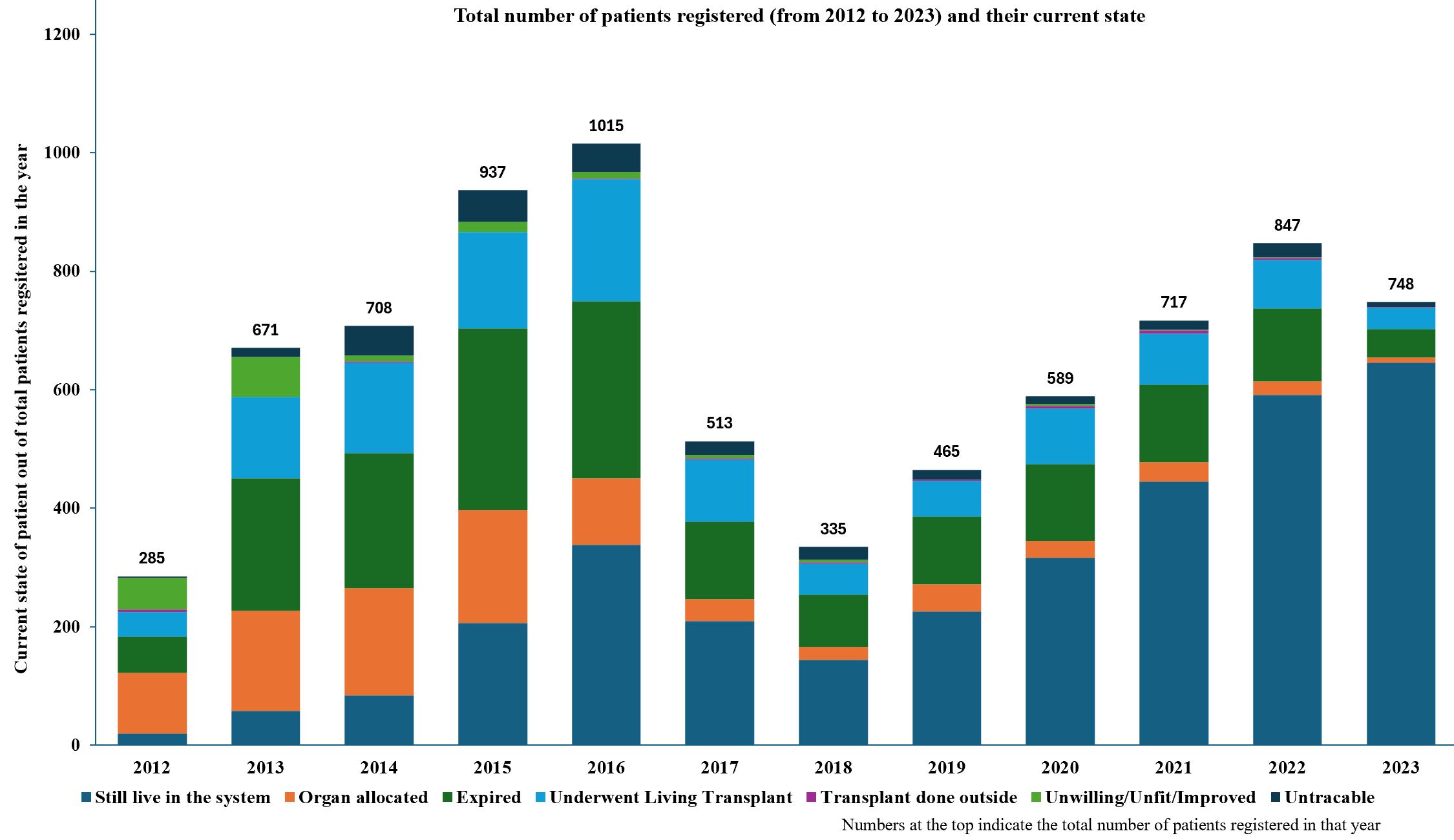

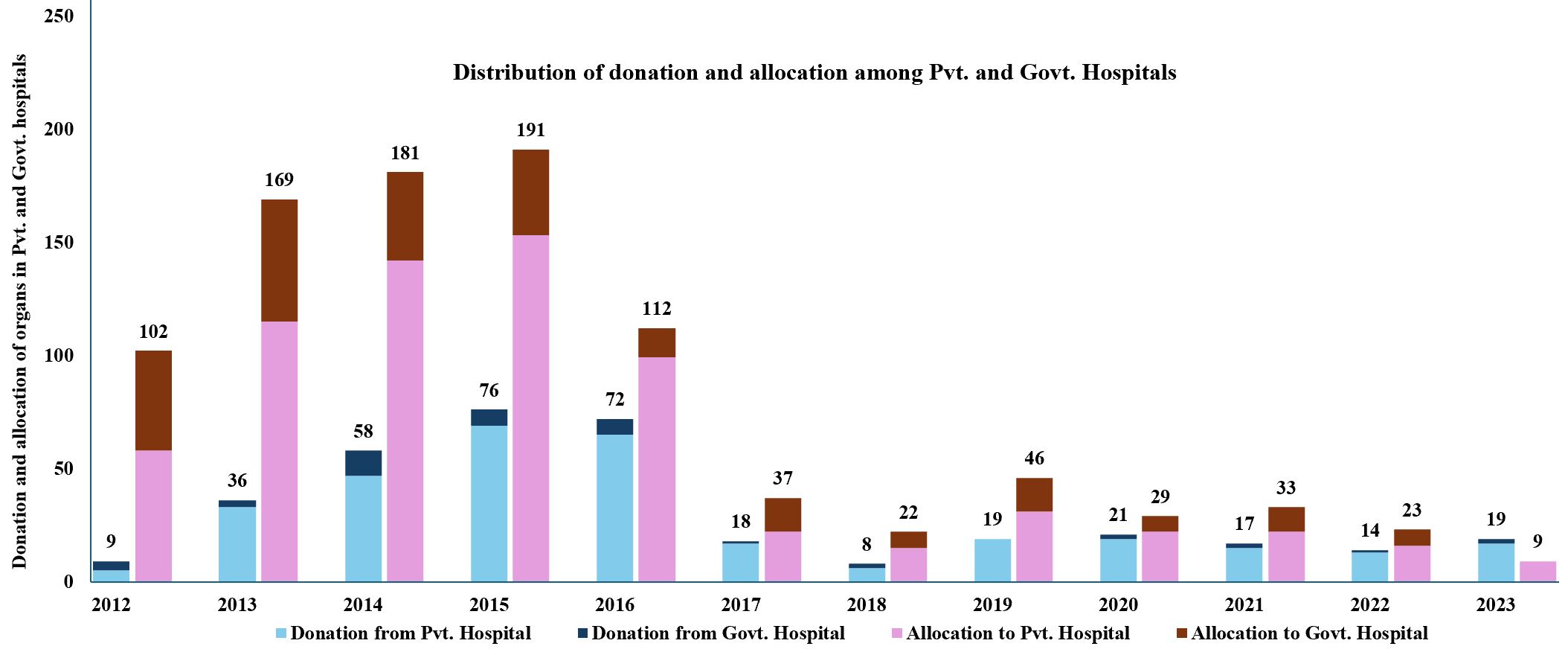

Results: In the last 12 years, a total of 7830 patients registered for transplantation. However, only 367 deceased donations happened in the state, and only 1024 solid organs were retrieved (~2.8 organs per donation on average) for transplantation. Discard rate of four major organs followed lung > heart > liver > kidney. Over 66% of the patients registered for a kidney transplant and nearly 31% for liver, rest 3% consisted of heart, lung, pancreas, and small intestine. Out of 7830 patients, nearly 1900 patients expired while waiting for a transplant, around 1000 patients were allocated a cadaveric organ, over 1200 patients got a living donor transplant, and nearly 200 people became uninterested or medically unfit (in a few cases, the condition improved as well) for a transplant. There are nearly 1000 patients who have been on the list for more than five years, waiting for an organ. Only 24% of all harvested organs were allocated to patients in public hospitals; the rest were allocated to private hospitals. For kidneys, the allocation ratio was around 40:60 between public and private; over 99% of all other organs were allocated to private hospitals.

Surprisingly, there has been a significant reduction in donations since 2017. From news articles, we concluded that a public interest litigation about wrong brain-death certification in late 2016 and a negative story in a movie in 2018 were the main reasons.

Conclusion: For a developing country with millions of patients with end-stage organ failure, improving the rate of donation is of utmost importance. Private hospitals are doing most of the donations as well as transplantation. In the absence of an incentive or accountability, non-transplant public hospitals do not put sufficient effort into identifying and persuading brain-death patients.

Department of Health and Family Welfare ,Government of Kerala. State Health Systems Resource Centre,Government of Kerala.

[1] program evaluation,deceased organ donation,organ allocation,