Enteric complications and their management in intestinal transplantation over the last decade in a single large adult centre

Subhankar Paul1,2, Andrew J Butler1,2, Neil K Russell1,2, Dunecan Massey1, Jeremy Woodward1, Charlotte Rutter1, Irum Amin1,2.

1Roy Calne Transplant Unit, Cambridge University Hospitals, Cambridge, United Kingdom; 2Department of Surgery, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Introduction: Performing primary bowel anastomoses in immunosuppressed patients is contentious, particularly amongst non-transplant surgeons, with many studies suggesting the use of stomas and delayed anastomosis. In intestinal transplantation (IT), however, where the patients are routinely subjected to high doses of immunosuppression and inotropes, there are few studies describing the enteric complications and their management.

Method: A retrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained database in a single adult centre performing IT between October 2013 and December 2023 was undertaken.

Results: During this period, 117 intestinal transplants were performed. Forty-four were small bowel (SB), 35 liver small bowel (LSB) , 27 multivisceral (MVT) and 11 were modified multivisceral (MMVT) transplants.

In all intestinal transplants, the pancreaticoduodenal complex was included, partly to increase vascular stability and also to allow preservation of the middle colic vessels to enable transplantation of the colon. All anastomoses were hand-sewn side-to-side double layered using a combination of prolene and PDS, except oesophageal anastomoses which were end-to-side.

Immunosuppression: Induction immunosuppression comprised of alemtuzumab and methyl prednisolone. Maintenance immunosuppression was initially with tacrolimus and steroids. This was followed by the introduction of an antimetabolite (mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine) with concurrent weaning of steroids.

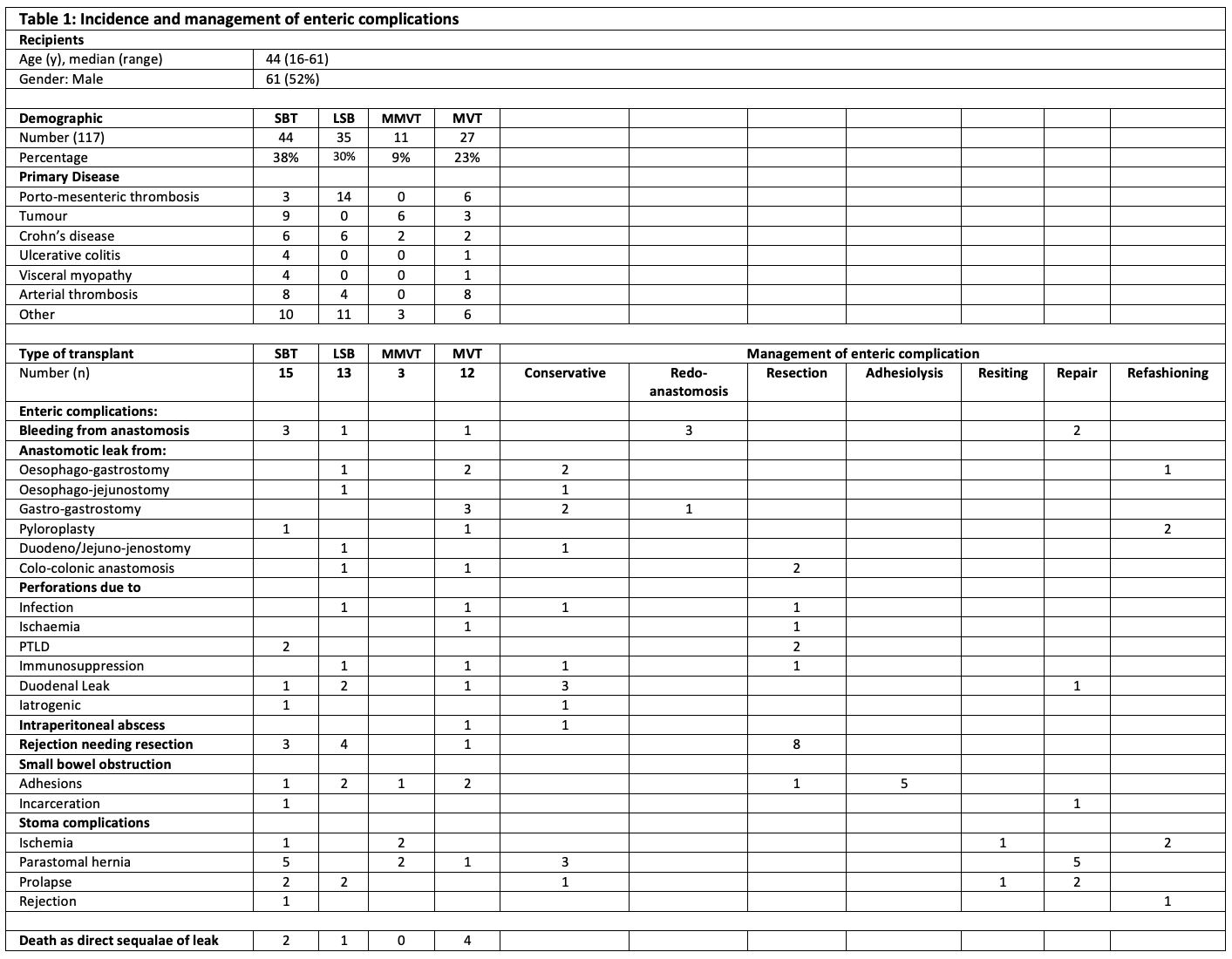

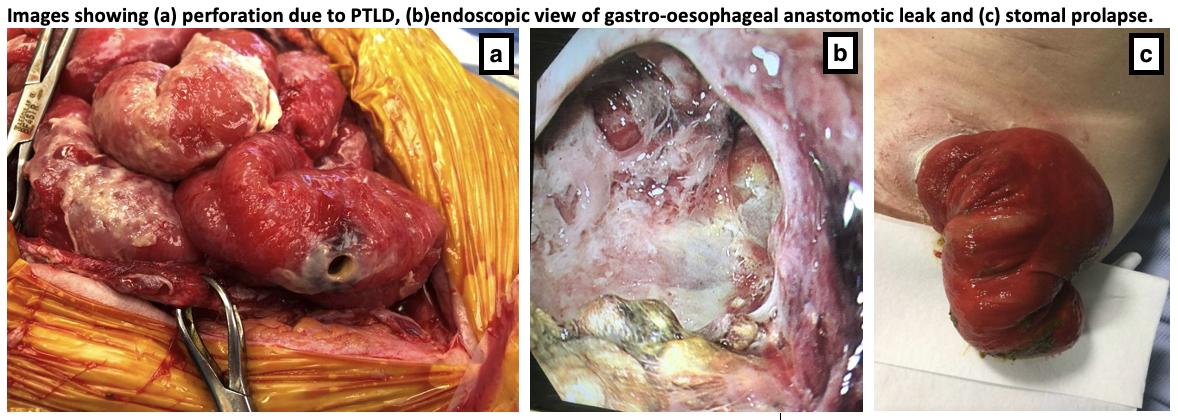

Enteric complications: Forty-three (37%) of the recipients had some form of enteric complications as outlined in Table 1. Anastomotic leaks, bleeding or perforations were the major complications. Eight cases needed resection due to rejection of which 2 were total explants. Seven recipients died because of sequelae of enteric complications. Thirty-four percent of the major complications needed resection, repair or refashioning of the bowel and another 32% of the complications were managed conservatively with drains or the use of endovac therapy. Seven cases presented with small bowel obstruction of which 6 needed adhesiolysis and 1 case was an incarcerated inguinal hernia containing transplanted bowel which was repaired, whilst 25% of stomal complications were managed conservatively.

Conclusion: From this analysis, we conclude that despite the immunosuppression, the rate of enteric complications following primary anastomosis in intestinal transplantation is low and can be managed appropriately on a case-by-case basis. In our experience, hand-sewn anastomosis is safe, however, a higher degree of suspicion is required as the symptoms and presentations of complications can be very different from non-immunosuppressed individuals.