Causes of racial disparities in living donor kidney transplant

Alyssa Pauquette1,5, Olivia Brado1,6, Glyn Morgan1,2,3, Oscar Serrano1,2,3, Bishoy Emmanuel1,2,3, Rebecca Kent1,4, Xiaoyi Ye1,4, Joseph Tremaglio1,4, Joseph Singh1,4, Wasim Dar1,2,3.

1Transplant and Comprehensive Liver Center, Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT, United States; 2Surgery, Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT, United States; 3Surgery, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Farmington, CT, United States; 4Medicine, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Farmington, CT, United States; 5Springfield College , Springfield, MA, United States; 6Trinity College, Hartford, CT, United States

Introduction: Minorities awaiting kidney transplant significant disparities in rates of living donor kidney transplant. Although recipient factors such as Social Determinants of Health (SDH) have been identified as a cause of these disparities, data regarding donor factors remains limited. To address which donor factors affected rates of living donor kidney transplant in minority recipients we undertook a review of the process of living donor evaluation at a single institution over two distinct eras: an era of conservative medical and surgical criteria vs a more liberal era. to determine whether medical and surgical guidelines versus SDH had an effect on the evaluation process for living donor candidates coming forward on behalf of minority patients awaiting kidney transplantation at our institution.

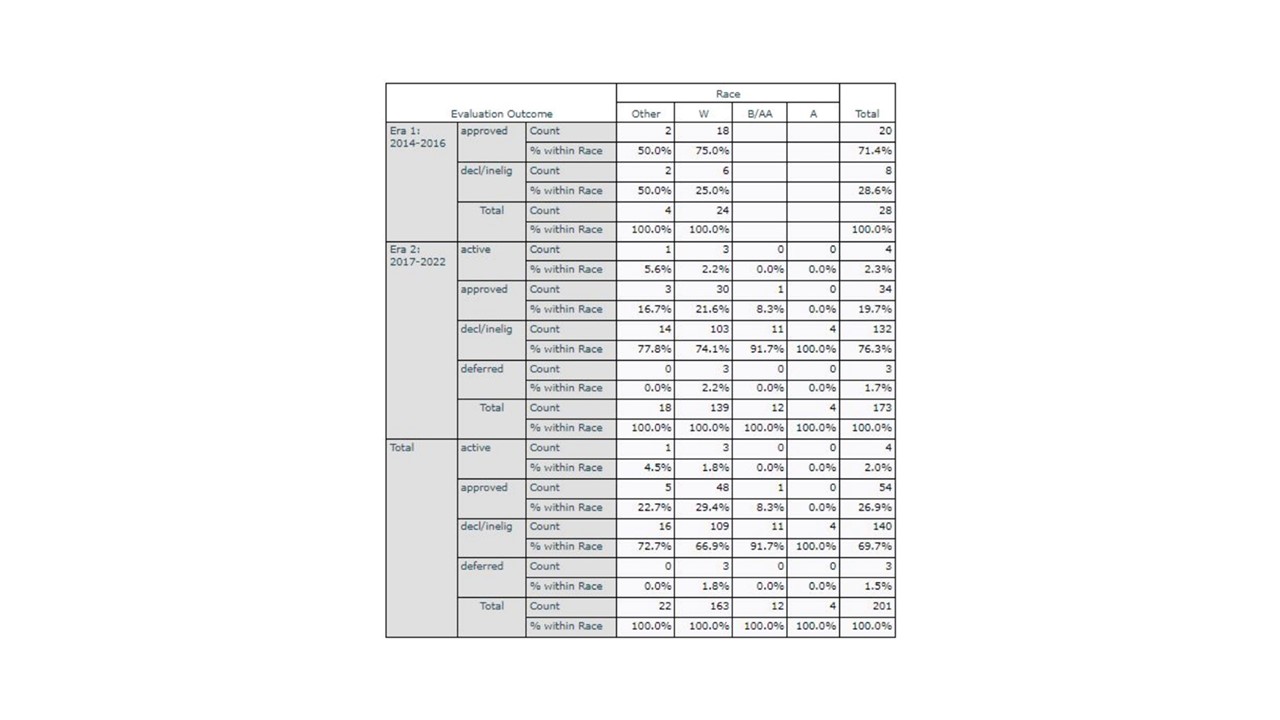

Methods: Patient records were retrospectively reviewed from two eras of LKDT, an era of more conservative medical and surgical guidelines (Era 1: 2014-2016) and a more liberal era (Era 2: 2017-2022). 201 donors for 165 potential recipients were identified. Demographics and evaluation outcome (approved, declined/ineligible, or deferred) were recorded. SDH, medical and surgical factors were assessed for influence in each donor outcome. Data was analyzed for statisticals significance.

Results: Total numbers of living kidney candidates evaluated were greater in Era 2 (173 evaluated) vs Era 1 (28 evaluated) but approval rates were higher. Era 1 (71.4%) compared to Era 2 (19.7%). In Era 1, no living donor evaluants were minorities. All kidneys from living donors in this era went to white recipients. In Era 2, 1 of 15 minority candidates were approved. However, in Era 2 minorities were declined at higher compared to their white candidates (Fig. 1). All kidneys donated in Era 2 by white donors went to white recipients. The minority donor donated to a minority recipient. SDH did not account for the differences in decline rates between white candidates and minorities in Era 2. The medical and surgical reasons for decline were present at similar rates across all groups in Era 2.

Conclusion: We examined evaluation of living donors in two different eras of medical and surgical guidelines at a single institution. Although the liberalization of guidelines led to an increase in total numbers of living donors evaluated it did not result in a proportional increase in living donor kidney transplants for minority candidates. This suggests that disparities in living donor kidney transplant in minorities are affected by institutional and societal factors. This suggests that liberalization of medical and surgical guidelines is insufficient to address health disparities in living donor kidney transplant and that significant institutional, and societal change to improve rates on living donor kidney transplant in minorities.

[1] Living Kidney Donation

Health Disparities

Social Determinants of Health