Paired kidney exchange program: A utilitarian service to the underserved populations in the northern great plains of the United States

Benjamin Limburg 1, Kaleb Dobbs 1, Els Reuvekamp 1, Sujit V Sakpal2,3,4.

1Sanford School of Medicine , Sioux Falls , SD, United States; 2Surgery , Sanford School of Medicine , Sioux Falls, SD, United States; 3Internal Medicine , Sanford School of Medicine , Sioux Falls, SD, United States; 4Avera Transplant Institue, Avera Health, Sioux Falls, SD, United States

Introduction: Incorporation of paired kidney exchange program (PKEP) has enhanced the scope of, and accessibility to, live-kidney donation (LKD) to rural and underserved populations in the Northern Great Plains of the United States. This study explores sociodemographic characteristics of LK donors and the PKEP’s transformational impact on LKD in the region.

Methods: Retrospective review and analysis of 1,776 individuals referred, evaluated, and donated at our transplant center over a 10-year period (June 1,2012–May 31,2022) were conducted. PKEP-affiliation began on Feb 1,2018, and comparative analysis was performed for pre-PKEP and post-PKEP phases.

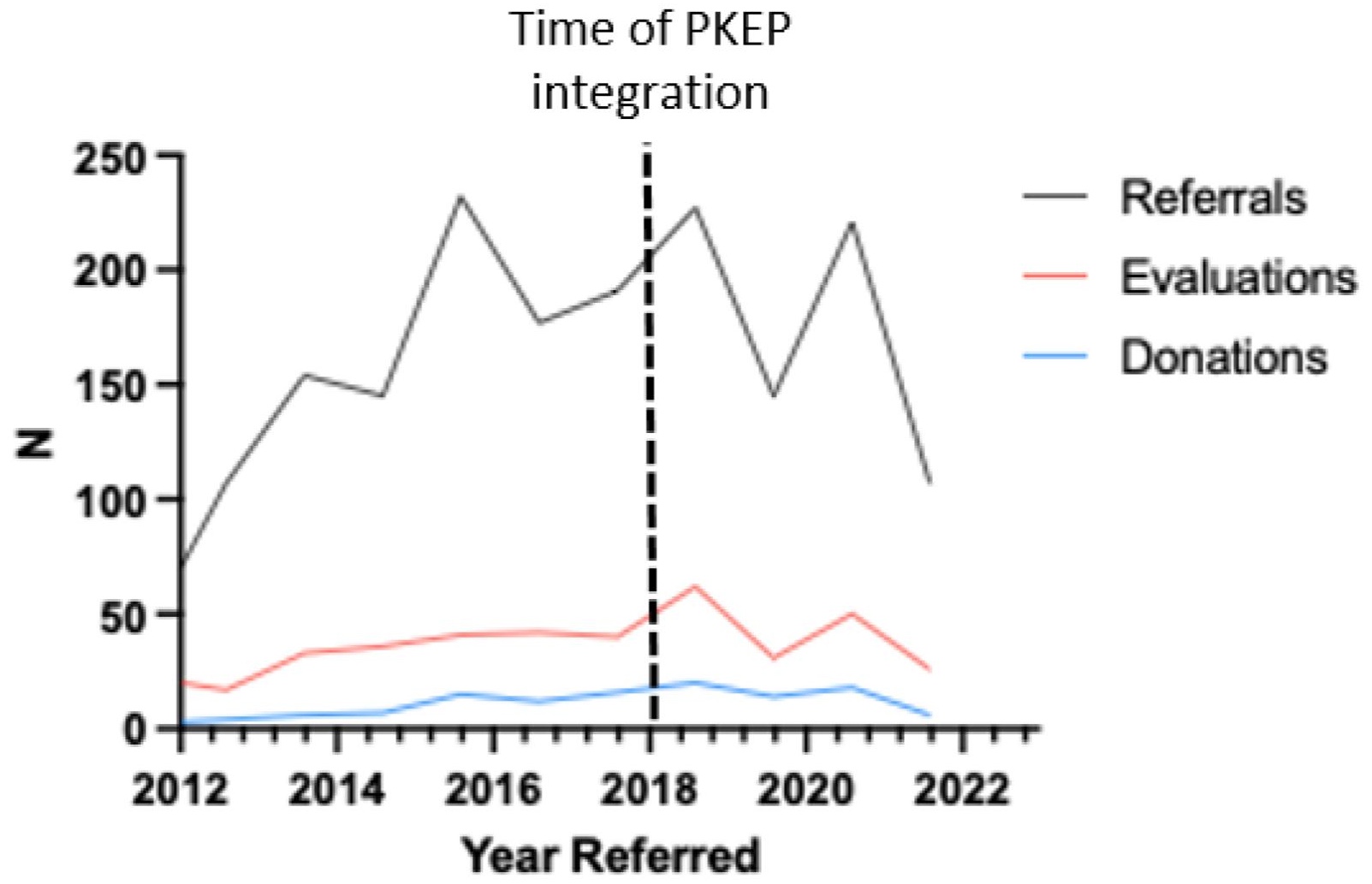

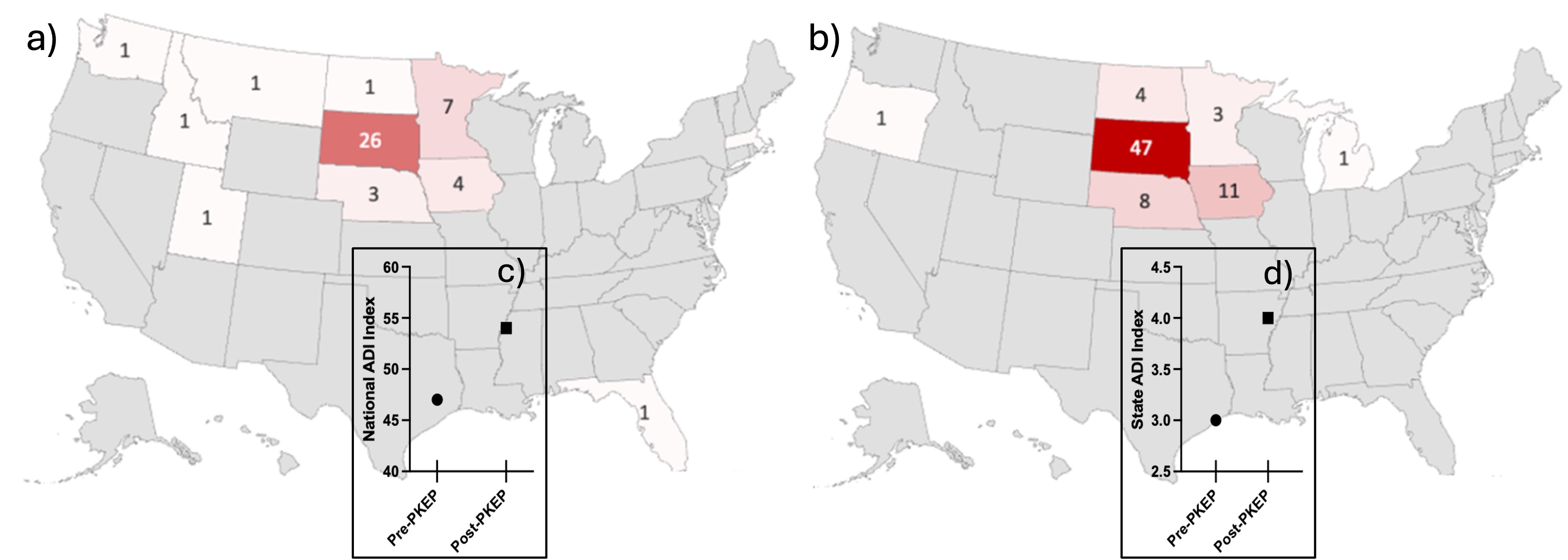

Results: In contrast to pre-PKEP (5 2⁄3 years), there were increased total referrals, evaluations, and donations post-PKEP (4 1⁄3 years) with a significant increase in referral-to-donation conversion (p=0.008, Figure 1). PKEP-affiliation enabled higher retention of in-state donors and appealed to those from neighboring states lacking PKEP-affiliated centers (Figure 2a & 2b). During both phases, individuals who were in a relationship, lived with cohabitants, attained higher education (Bachelor’s degree at minimum), employed, or had a dependent seemed more likely to donate, however, this was confounded by unspecified data within those categories from numerous pre-PKEP referrals. This said, compared to pre-PKEP, the post-PKEP phase demonstrated a larger proportion of donors from disadvantaged socioeconomic neighborhoods (median area deprivation indices 47 vs 54 [p=0.056; Figure 2c] nationally and 3 vs 4 [p=0.055; Figure 2d] at state levels, respectively) and rural counties (38% vs 50% [p=0.099], respectively). Post-PKEP, more women came forward (70% vs 60%, p=0.02) and donated (73% vs 66%, p=0.51); more Indigenous People donated (5 vs 2, p=0.72) despite reduction in referrals (67 vs 121, p=0.04); and a steep rise in non-directed referrals and donations transpired (13% vs 3%, p=0.01 and 12% vs 2%, p=0.04, respectively). While medical comorbidities and variant renal anatomy excluded the majority of donor candidates at evaluation in both phases, significantly more were lost to follow-up post-PKEP (44% vs 21% pre-PKEP, p<0.01) prior to evaluation. After evaluation, 32.7% of potential donors either self-retracted or had an unacceptable blood or tissue type in pre-PKEP phase compared to 25.1% of potential donors in post-PKEP phase (p=0.027) which included those who opted out of PKEP.

Conclusion: PKEP integration boosts LKD and potentiates kidney transplantation access to rural, underserved regions in the United States.

[1] Live-Kidney Donation

[2] Kidney Transplantation

[3] Paired Kidney Exchange

[4] Rural Healthcare

[5] Healthcare Equity